Going into a public toilet is sometimes not for the faint hearted. Not only could there be visible evidence of previous use, but also the unseeable germs that may lurk on surfaces.

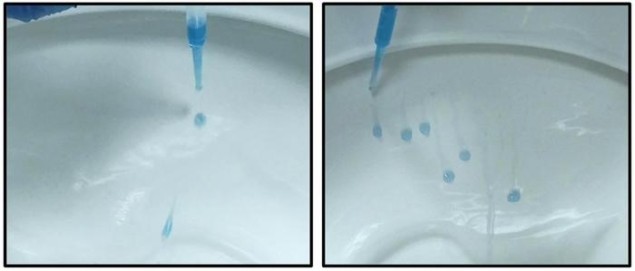

Now researchers in Germany and Turkey have come up with a new transparent coating that makes porcelain more water-repellent and toilets cleaner. They used an oil containing the silicone polymer polydimethylsiloxane, or PDMS, and milled the solution for an hour with small tungsten carbide balls. This process breaks apart some of the polymer’s chemical bonds so it forms a durable, oily layer.

After applying the milled oil to one side of a sterilized toilet bowl, with the other half left untreated, they then poured human urine combined with E.coli and Staphylococcus aureus into the toilet. When swabbing what was left behind on both halves of the bowl, they found that the PDMS-treated area stopped 99.99% of the bacterial growth that was seen in the other half. The work could finally put an end to making a visit to the toilet such a shock to the cistern.

The research is described in ACS Applied Material Interfaces.

Sticky ice

While slippery toilet bowls seem like a great idea, slippery ice can be a bad thing – unless you like ice skating or operate a ship in the Arctic. Like many properties of water, exactly why some ice is more slippery that others is a bit of a mystery. Now, researchers at the University of Illinois Chicago have studied the stickiness of ice that contains common substances including salt, soap and alcohol.

â€Å�Be it dirty sidewalks or the hull of Arctic-going ships, there’s always impurities [in ice],†explains team leader Sushant Anand. â€Å�So, the natural question that comes to mind is: What is the influence of these compounds on how strongly ice sticks to surfaces?â€Â

The experiments revealed that pure ice is much stickier than ice containing impurities, under certain circumstances. The stickiness, or slipperiness, of ice depends on a quasi-liquid layer that occurs on the surface of the solid material – and this layer is notoriously difficult to study. The team did molecular dynamics simulations that suggest that when water freezes, impurities are pushed towards the surface, where they enhance the quasi-liquid layer.

Arctic mystery

However, this discovery led to a another question – if a small amount of salt makes ice less sticky, then why does frozen seawater stick to the hulls of ships? The answer, according to the team, is that ice freezes on hulls slowly. This affects how impurities are distributed within the ice, reducing the concentration on the surface – making the ice more sticky.

�Our study represents just the tip of the iceberg, opening new lines of investigation of how impure ice adheres with widespread implications across multiple disciplines,†Anand says.

The team reports its results in Materials Horizons.