On August 9, 2023, the International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples, WLT editor in chief Daniel Simon spoke with Wilhelm K. Meya, chairman and CEO of The Language Conservancy (TLC) about the nonprofit’s remarkable work of helping to revitalize Indigenous languages. Their conversation, which took place over Zoom, has been edited for clarity and length.

Daniel Simon: To begin, could you tell us about your founding vision for The Language Conservancy and your ethos of supporting Indigenous language communities?

Wilhelm Meya: The Language Conservancy is a nonprofit organization based in Bloomington, Indiana. We’ve been actively working with Indigenous and endangered languages since 2005 and are currently working with over fifty languages, predominantly in the US, Canada, Australia, and Mexico. Of course, there are many hundreds of languages in North America that are in danger of extinction, and we’re working diligently to support those languages. But overall, worldwide, there are nearly seven thousand languages. Over the next fifty to one hundred years, it’s estimated that about 90 percent of the world’s languages will become moribund or extinct.

Wilhelm Meya: The Language Conservancy is a nonprofit organization based in Bloomington, Indiana. We’ve been actively working with Indigenous and endangered languages since 2005 and are currently working with over fifty languages, predominantly in the US, Canada, Australia, and Mexico. Of course, there are many hundreds of languages in North America that are in danger of extinction, and we’re working diligently to support those languages. But overall, worldwide, there are nearly seven thousand languages. Over the next fifty to one hundred years, it’s estimated that about 90 percent of the world’s languages will become moribund or extinct.

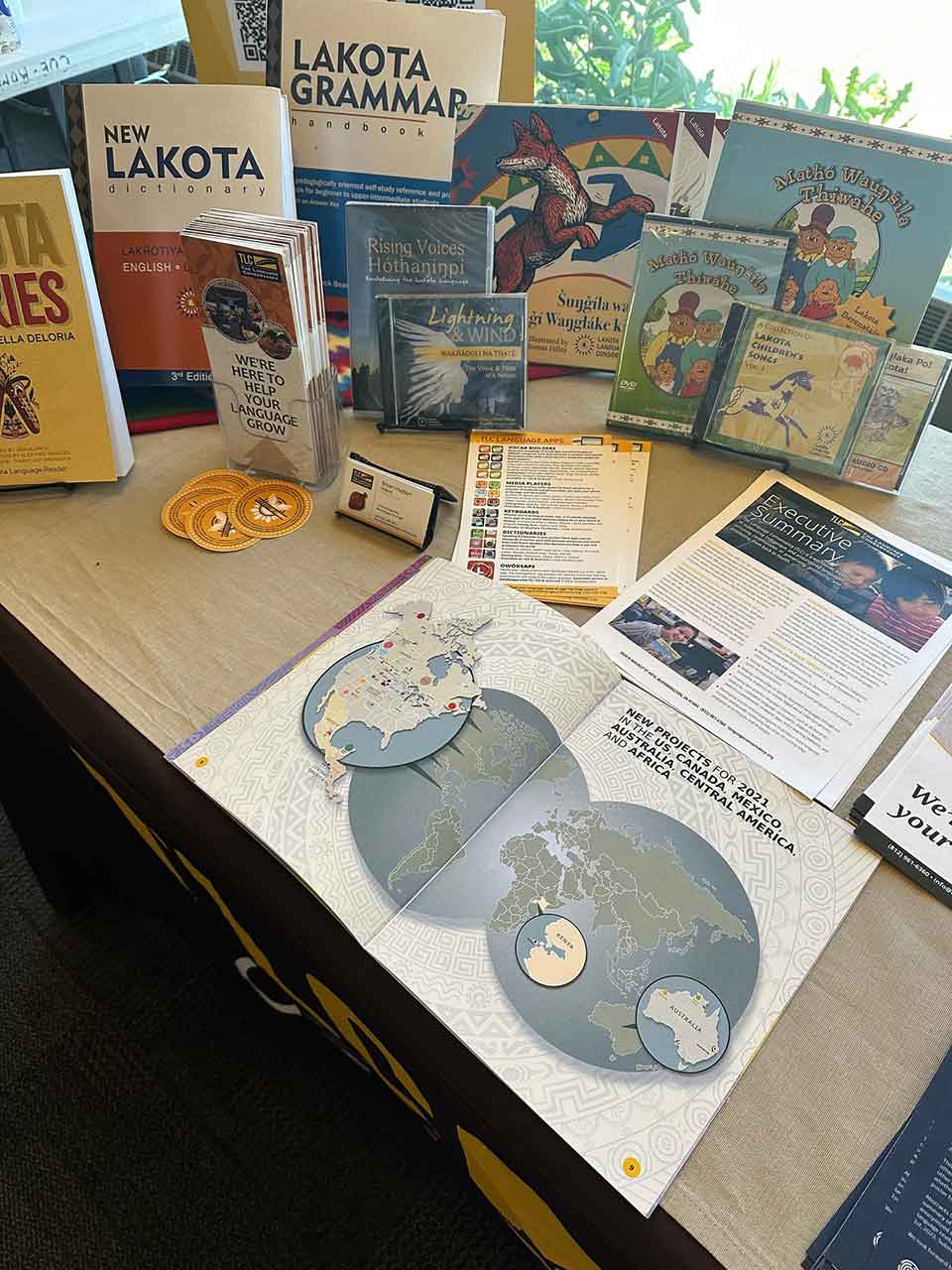

The Language Conservancy works as a technical support organization to support communities who hope to maintain or revitalize their language, and we do that through many different kinds of avenues. We help build dictionaries, train teachers, do e-learning platforms, cartoons, apps, and picture books. There are hundreds of different materials and resources that we help communities develop so they can teach and learn the language. Language is such a delicate thing, something very appreciated by the community in a deep, profound way, so we take the responsibility of caring for these languages very seriously.

We see ourselves essentially as a bridge between the generation of Elders, who are the language keepers of their community but—for different reasons, over the last fifty years—have not been able to pass the language down to their children and grandchildren. TLC is essentially a bridge between that generation of speakers and those young people who want to learn the language and want to have the resources that are needed to effectively move forward with the language. We do that in a very respectful way. We try to provide the resources and essentially bridge the language between those two generations so that the young people can move forward with dignity and have the language for themselves. Of course, the Elders themselves feel fulfilled that they have done their duty and passed on the language to the next generation in a way that is accurate and viable.

When language shift happens, essentially the clock starts ticking on that language because it’s not reproducing its speakers anymore.

There’s this phenomenon when a language is passed down between parents and their children. It’s called intergenerational language transmission. It’s a natural process that has occurred for hundreds of thousands of years in almost every language. But for different reasons, due to government policies and other assimilation policies in North America, languages essentially stopped being passed down in the mid-1950s. That moment is called language shift. When that happens in a language, the clock starts ticking on that language because it’s not reproducing its speakers anymore. The real number of speakers of any language begins to decline because people are passing on, and no new children are growing up speaking the language. Fast-forward seventy years from the mid-1950s, that’s where we are today, where the speakers of the last generation are in their mid-seventies. That creates a very small window of opportunity to document these languages to provide continuity between the learners who want to learn the language and the last speakers. Our hope and dream is to create a generation of speakers who can speak with the last generation of first-language speakers.

That’s our goal in the way we work with communities: how do we accelerate the learning process so that there is some continuity between the people who can say, “Yes, I did communicate with a first-language speaker”? That’s really where we are in terms of our work in North America, trying to take this very acute situation, where language is in some ways on its way out in most of these communities, and provide them with the resources they need to learn these languages. Hopefully, some of these languages can be saved. That’s the context for us, in the US and Canada as well as Australia.

These particular places—the US, Canada, Australia—are forty or fifty years ahead in terms of the overall wave of extinctions that are going to be happening over the world. In our work in Mexico, for example, we notice that language shift moment, depending on the language, happened anywhere between the 1980s and ’90s. That gives us an extra forty years, essentially, to begin putting the resources together so that these communities have what they need to teach the language, develop literacy, and create materials. In some cases, the demise of these languages has taken fifty to eighty years. We can’t just snap our fingers and hope to create generations of speakers overnight. Revitalization and rehabilitation of these languages is generational.

We can’t just snap our fingers and hope to create generations of speakers overnight.

Our vision is to support Indigenous and endangered languages worldwide as we move forward, community by community, developing and furthering our skill set, and being able to serve these languages in a more productive, efficient way. It’s a topic that is relatively unknown worldwide. Climate change is something very front and center, but the worldwide extinction of languages—and with those languages, the cultures, and all the other things associated with language—is basically unknown. This is something that I think we really need to begin taking seriously and ringing the alarm bells for.

Simon: That’s actually something that World Literature Today, the magazine that I edit, has really been trying to foreground, especially in recent years. I should note that the maps on the TLC website really visually represent that state of loss over the past century in places like Australia, Canada, and the US. Of course, the boarding school phenomenon was a big part of that. Here in Oklahoma, there have been a lot of efforts toward preservation and revitalization. I was excited to see that TLC is working with the Seminole Nation and the Lenape, Wichita, and Maskoke languages to extend that work into the state. Thank you for those maps and for those resources that are on your website, which I found really helpful, especially for our new issue called Indigenous Literatures of the Americas. We’re really trying to focus on that question of language with many of these pieces that will be in the issue, translated from various Maya languages, from Quechua, from Osage, and other languages throughout the continent. We’re really excited about presenting that work.

Meya: I love it. For us, that’s a dream. We focus so much on literacy. We cannot do this work without the written word. The focus on writing and reading, learners require that and need that. But beyond that, as we develop the second language learners, we really want to develop the literacies and literatures in the language. So, for Lakota, for example, we have a number of leveled readers we’ve been working on, and we’re doing some advanced stories written by Lakota authors. More and more, we’re trying to develop a nascent body of literature for these languages.

Simon: Coincidentally, today happens to be the International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples. Obviously, TLC celebrates Indigenous languages 365 days a year. But is there something about today that you find especially symbolic or worth noting?

Meya: Again, I feel like we’re working in a space that is marginalized. There’s not a lot of awareness around language, and we often say that as we’re working in a space with Indigenous issues and languages, both of those topics are not front and center in the US, unfortunately. Whenever we can bring more attention in a positive way to the work that we do, to the work that communities are doing to bring back their languages, those stories of hope, that’s what we’re interested in. For us, it can feel quixotic at times, working to try and save thousands of languages, some with perhaps just dozens of speakers left. And some of them—the vast majority of the hundred languages left in the United States—have less than fifty speakers. That’s what we’re dealing with.

It can feel quixotic at times, working to try and save thousands of languages, some with perhaps just dozens of speakers left.

But at the same time, we’re focused on hope. We’re focused on the positivity around language, the healing that language can bring to communities as they begin to create positive identities associated with the language—that is so important to us. I recall that we worked with a language in the Pacific Northwest where the language had not been spoken since the mid-1960s. Luckily, there was a linguist who had done a number of word lists, worked with the last two speakers, and recorded all those word lists, but they were mishmashed, all over the place, across numerous areas. Over the last several years, we’ve brought all of that together for this community. We put it into an app that’s accessible, easy to learn. Now we’ve got learners and speakers—not fluent but proficient—of this language that hadn’t been spoken in forty or fifty years. That’s a little bit of a miracle when you see something like that—you know how long it’s been since that language was doing something, that people are speaking it or learning it again. That’s hopeful.

That means we can do that with any language. If there’s a will, there’s a way for these communities—we just want to make sure that they have the resources to do that. I also like to say that for every language, we want to make sure that there are enough materials and resources so there is no way not to learn the language. That’s the world we want to create for every one of these communities—that they have all they need to learn their language, and that’s what we’re trying to provide. That goes for dictionaries and apps, video resources, as well as picture books. There has to be something for everybody. Language is an intergenerational effort; it’s a team effort. This is a relationship, a partnership that we have with communities, and every community is different. We need to make sure the Elders are involved, and parents, grandparents, young adults, high school and middle school kids as well, all the way down to preschool. And we need to have something for everybody because there needs to be points of engagement for them.

Simon: Could you say a little bit about the rapid work collection model that you use?

Meya: The rapid work collection (RWC) model has really revolutionized our ability to develop dictionaries. Typically, we use a modified RWC process, a digital rapid work collection that is essentially computer-based, and it has a computer interface based on an old model called RWC that was used by SIL International in the 1980s and ’90s in Africa. In the old days, developing a dictionary would take about twenty years. A single linguist would typically go to a community and work with one or two consultants, go back to the academic setting that they were in, and then come back again each summer. It would be an excruciatingly long process. As I mentioned before, we have a very short window of opportunity to document these languages—just fifteen years for most languages before the last speakers pass on. RWC really filled that void in an amazing way.

In the RWC process as we do it, there’s a long a build-up and a real orientation and a back and forth and Q&As and open houses and information sessions. Once that all gets done, we’ll go to a community, let’s say we’ll work with about thirty or forty Elders. We’ll divide those Elders into ten groups of three or four people. They’ll each get assigned a station with a computer, a linguist, a microphone, and anything else needed. Then they’ll get these domain lists or categories. The RWC process relies on going through 1,700 categories of all the different topics you can imagine, from baby language to traditional medicines, to building materials, to diseases, to feelings, and on and on. So, when these groups get a list of topics, they’ll go through each topic and it becomes a fun game.

So, if I was going to do an RWC in English for you, I’d ask you, “What are the things you might find in a kitchen?” When I ask you that, your brain’s going already—it’s going to be pots and pans and tables and chairs and a stove and spoons and knives and on and on. You might come up with a list of forty or fifty things. How Elders see it, it just becomes this, almost like Scrabble, but it’s just a fun game. They will come in there and the words from a topic two days ago and they say, “Hey, I just remembered this other one; we have to add it to the list.” Every day we’re generating 1,500 words across ten groups, totaling around 15,000 words over ten days. And that is the start of the dictionary. Then, there’s a whole other ten to twelve months of cleaning up the audio and transcribing, going over inconsistencies, and cleaning up the data.

Then, at the end of that process, it will be put together in a database and in an app that you can listen to. You can type in any word you want and you hit a button, and there it is. You can press another button, and there you’ve got the audio for it. And that’s an amazing thing. Suddenly, you have access to all of the lexical data of this language right at your fingertips. It’s a total game changer, because not only do you now know how to spell all those words you can hear, but a learner can look at it, hit the button, and then hear the word spoken, so they feel more confident about even reading it. Young people often say that the app is so powerful, it’s almost like having their own grandma or grandpa in their pocket. They can pull out the app, and often it is their grandpa or grandma saying what the word is.

Young people often say that the app is so powerful, it’s almost like having their own grandma or grandpa in their pocket.

The beautiful thing is that the process itself is so cathartic for the Elders. It’s like this profound feeling of having left the legacy, a profound sense of responsibility that’s been taken care of. Fundamentally, when an RWC happens and the dictionary is released, not only is it the cornerstone of everything else that needs to be built out, from apps to textbooks to whatever, but this will serve the community for generations. It’s a way of creating a living legacy for the future. The impact is only going to compound in its profoundness as we move forward across all these languages. And we see that already.

Simon: How wonderful. You must be excited about the upcoming ICILDER Conference in Bloomington in October. What are you most looking forward to?

Meya: ICILDER stands for the International Conference on Indigenous Language Documentation, Education, and Revitalization (October 12–14, 2023). This is going to be the first, we hope, in an ongoing series of ICILDER conferences. This is one of the official conferences of IDIL, which is the UN’s International Decade of Indigenous Languages. Fundamentally, language work is really about hope and positivity. And there’s so much work to do, and there are so many of these language warriors, language champions, language workers doing that work in isolation, often siloed. We might work with the community in one place or another. We’re doing great work, they’re doing great work, and they’ve just done this amazing thing. They might have done an RWC, but they have no one to share that with. This conference brings together those partners who’ve been doing this work in isolation and allows them to share their experiences, allows them to grow and inspire others.

What I’d like to see happen—and we’ve seen this already last year when we did a little mini-conference along these lines—is that when these partners come together and share that experience, it has this multiplier effect of inspiration. Because when you bring together, say, eight communities that have used RWC to create dictionaries, then the ideas start multiplying. Likewise, with communities that are doing textbooks or apps or e-learning platforms, this is an opportunity for them to share some of the best practices that they’ve done in the use of these materials and the development of their projects. We hope that this inspires continued work and development across all these lines.

A lot of the partners are going to be there, but also folks that are not partnering currently with TLC, which will allow them a chance to see the work we’re doing. We also hope to bring funders so they can hear directly from community members about the profound impact language projects have on communities. Again, it just inspires a way of working together that’s cooperative for us: language revitalization work is a team effort. I think it requires people from all across the spectrum, from academics and department heads to IT people, organizers and event people, community members and Elders in different communities and tribal leadership, people and politicians, policymakers, all those people need to come together around this issue. And that’s really what we’re trying to do: let people know that this is not just a thing that gets done in isolation.

If we’re going to do this seriously, we have to bring a lot of resources to bear on it and get people focused on the idea. Because I think intuitively people get that language is important, but why is language important? Fundamentally, it’s at the nexus of so much of our human experience. It’s how youth express themselves. It’s the humor, the education, the art, the prayers, the songs—it’s all of that. It’s so much of a human experience. We take it for granted in the monolingual world of English that language is just a vehicle for how we express ourselves. But people who speak more than one language realize that each of those languages is also a different worldview that needs to be nurtured as well. Because within those worldviews exist the beauty of life and the nuance and the subtleties that may not exist in one language. We want to make sure that there is a space for that.

People who speak more than one language realize that each of those languages is a different worldview that needs to be nurtured as well.

Fundamentally, we believe that everyone in the world should be able to not just speak the dominant language that provides the most utility for participating in our globalized world, but also speak their heritage language. There’s a space to be able to speak multiple languages, and humans have been able to do that for hundreds of thousands of years. Why are we stopping now?

Simon: So, anyone in the general public can register for the conference and attend in person?

Meya: Yes, I encourage everyone to attend. It’s such a wonderful opportunity for anyone interested in language, interested in this space, and really in the cutting edge of what The Language Conservancy is doing. It’s not just The Language Conservancy, but its partners and all these communities we work with who are doing such amazing things, moving things forward in ways that haven’t been done before.

We’ll have some wonderful keynote speakers as well, like Sir Tīmoti Kāretu. He’s the commissioner of the founders of the Māori language revitalization effort in New Zealand, which is the Indigenous language that has had the most progress made in terms of its own revitalization over the last sixty, seventy years. He was instrumental in the founding of it, and they’re ahead in trying to revitalize their language. When he speaks, he’ll provide a lot of context, inspiration, and hope because he’s seen many of these processes unfold. And he can provide a glimpse into the future of what language revitalization looks like and hopefully inspire other communities moving forward. We hope this conference accelerates the efforts that are happening worldwide.